[Instructional Hoops for Sale from Pearson]

I started out thinking I could assert that the school curriculum (the "what" of instruction) is irrelevant but that is of course not what I would mean to say.

Rather, curriculum is ALL possible responses to all possible utterances.* That means the space of instruction (fancy critical theory calls this the "scene")--home, church, playground, friend's home, school bus, school, classroom, hallways, iPad, laptop, Xbox, etc.--and everything flowing into and out of it, is curricular content. Content is utterance and response. It is what we allow to be uttered and what we allow to be a proper response that is taught. In other words, no matter the content, it is convention that is taught/learned.

Curriculum is defined as a course of study--this implies intention and choice, and by definition, exclusion.

ALL that we experience "instructs" us. Until our brains choose a template that is. Then we ignore instructions as a matter of course. We are, so to speak, instructed to ignorance.

Our oldest child said recently while lying in bed listening to the final installment (at last!) of The Alchemyst, "Why do we learn so much math at school?" That morning he had been stumped (along with his old man) by a particular problem on his homework. I advised he just put a question mark and admit he couldn't figure it out. That's what's school's for anyway, right? It's a chance to learn what it is you don't know and begin the process of searching for answers.

It was in reflecting on that question mark that he began his search for the school's rationale for focusing so much of their time on math.

I had an answer for him. "Because math is easy to test and grade. Because math is black and white. Because math is right and wrong. And because math is the basic tool of measurement. And because measurement is how we manage populations." I did not say, "Because the plastic and skeptical mind is the product of language and not of numeracy. The more you focus on math, the less you focus on what is truly and profoundly human. Because to be manipulated by language you must not know how language works. The more math, the less language, the more docile and servile the product ("sum") we call citizen." I asked him to consider our road signs. Black and white signs indicate legal limits; yellow signs are suggestions of caution (at your own risk you may ignore these); red requires the greatest attention and is an indication not only of law but of danger and risk for the community. We can create algorithms (and insurance companies do as do university economics departments and transportation engineers) to show how our driving is patterned by these signs and the results of abiding or ignoring these signs of authority. But unless I describe the algorithm and what it intends to show, the algorithm is meaningless.

I told him not to worry about it. But he was (is) and he pressed, "What about college, and a job?" Having never done well in math myself (probably no better than he's doing) I simply said, "I went to college; I got a job. We've done okay, right?"

***

"...very advanced for its time, was Darwin's notion that a scientific law is a mental convenience....a scientific law becomes a linguistic convenience, or at best a mathematical convenience, the latter being preferred, for mathematics is empty of content. It can meet the criteria of logico-mathematical convention and can with impunity create new criteria because it does not say anything, in the sense that a natural language says something." (Morse Peckham, "Romanticism, Science, and Gossip.")

***

Yesterday I watched a class of kindergartners absolutely make a muddle out of the concept of "whole" and "part." Most things are "in themselves" both wholes and parts. I don't find any reason to teach this kind of thing. A dollar is 100 pennies, or 4 quarters, 10 dimes, 20 nickels; is your 5-or 6-year-old using money? I'm fairly certain these are concepts that require the brain to have developed to a particular stage. This is why we admit that some kids "get it" faster than others--their brains have simply developed to a more advanced stage. Why do we bother? It seems plausible that teaching meaningless content actually serves to retard development.

Taking "lessons" "out of context," as it were, seems useless and must feel useless to those employed to convey them. What are we teaching when we, day after day, instruct the 7-year-old in the uses of the "signs" of punctuation? Why, by age seven, do we need to be able to discriminate punctuation on tests when we likely have no clue of the meaning of the very words we're punctuating? If it starts with Who, What, When, Where, How, or Why, be sure you write a question mark! (I said with emphasis and thus used another instructive sign.)

Stages of learning require "groundwork" you might answer. But I think this is hooey, or at least the way we "lay groundwork" is hooey. All of life is "groundwork" for intellectual processes and we can certainly learn in many ways. Abstractions in elementary school seem less than healthy to me.

***

The Principal, a man, comes out into the hallway and approaches a group of five kindergarten boys. One of the boys had been making loud growling and roaring noises, the others, laughing and talking. The man, 6 feet tall and of athletic build, tells them their behavior is unacceptable and inappropriate, disturbing other students as they work in their classrooms and disturbing him as he works in his office. The boys stand, motionless, and stare up at him, most of them have their mouths open. The growling, roaring boy has his firmly shut. Is appropriate behavior the instruction? Or is it rather that the Principal is a large, scary man? Like the dogs they are at this age, they will forget and need a repetition of a training stimulus.

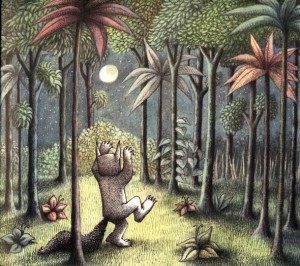

If behavior is not controlled, it becomes random. The control of response is essential to the human enterprise. But ultimately response can be controlled only by force. Culture is defined as instructions for performance; or, culture turns behavior into performance. Meaning, it is proposed, is sustained by redundancies, the constant reiteration of cultural directions….Without that redundant reiteration behavior disintegrates. (Morse Peckham, Explanation and Power.)In the age of constructed and limited environments (tightly controlled) passed off as unlimited fantasy machines, i.e., the computer and its digital spawn, it is a gift to find randomness at all. Long live the growling, roaring child who stalks the hallways with hands shaped into claws and eyes wide in performance. It is this behavior that we step on rather find a way to channel. We want our students to be like the gray-pink pork under cellophane at the grocery store--no variation, no flavor, bred to predictable consistency...we'll let you know if you get to handle the spice rack as an "enrichment" possibility. Perhaps we fear the wildness in one will be a kind of nitrogen-fix for the other withering and wilting children in our hot-house schools.

Long live the wild things allowed a wilderness of unconventional thinking; long live the adult, the parent, the teacher, strong enough to love them and reinforce their wildness, and, of course, to keep their dinners warm.

***

*An immersion in Peckham makes it hard not to use his terminology.

Note: I have to admit that I find the worksheet serving to illustrate this post baffling as pedagogy. Any thoughts out there? This math exercise seems bent on creating another kind of abstraction to serve as an interim to understanding a simple equation. It somewhat mimics grade 1's "fact triangles" and yet works against reinforcing that by changing the instructions and the visual cues.

Illustrations: 1. worksheet a Pearson production--a truth, the first priority is to sell materials in a market. 2 and 3. out of Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are.

This is important. Our schools are turning the wild things into pale pork sealed in plastic. . . because that's the way the Business Roundtable, Bill Gates, the Republicans, and the Democrats want it.

ReplyDeleteThanks for writing, Susan. Agreed, of course (and I've used your work on more than one occasion--here is one instance: http://wp.me/p1JTwx-HV).

DeleteI think Sheldon Wolin (a philosopher being popularized somewhat in the last few years by Chris Hedges) mentions something in his most recent book "Democracy, Inc." about the ways in which the workers and middle managers and CEOs operate "of a piece"--that most if not all of us are simply doing what we think is right as the system defines it and rewards it. That there is no intent to do harm--we simply trust our "way of living" to make it right.

Peckham calls this the maintenance of an incoherence and claims that this is what culture IS. It's when the coherence begins to lose its stabilizing power that a new coherence is created and it can be anything as long as it offers an explanation. These explanations do not often stand the test of exemplification and this is why so many who won't "buy" the explanation act as if those who do are idiots--they disprove by examples and so show the true incoherence. Yet, the explanation can still stand as long as the "high culture" that serves that incoherence can keep up the facade. Hence Limbaugh, et al. But this serves too for a progressive "usurpation" of labor energies and "human capital"--Stephen Pinker is a good example of the "liberal" attempt at another kind of "coherence" that is simply a myth to serve social management.

What is unlikely is that any of these parties can agree that ALL is incoherence as there are no "ultimate" answers. This is why we cling mightily to God and Science as Explanations. It is unsettling to see oneself as a "randomization" engine!